First of all, what is the aim?

Here, I consider concepts as a means of exploration and – as a set – as the basis for arguing why the final design embodies/is based on the concept that is does/is.

What if we take the game SET as an analogy for how your concepts should differ.

When ONE aspect varies, you have something that looks like a controlled experiment. You’re changing one variable and seeing how that impacts the design’s properties and performance. Of course, when ‘one’ aspect is different, many more aspects will also be different. The world (and thus, physical artefacts) are infinitely complex.

When MORE THAN ONE aspect is varied, you either have to do the full combinatorics or find some way in which different choices in those aspects hang together (in effect, going back to the situation where only ONE overarching aspect is varied). Or, if there are no significant interaction effects between the aspects (sub-functions, domains, components) then it’s better to decouple them and decide per aspect which is preferable.

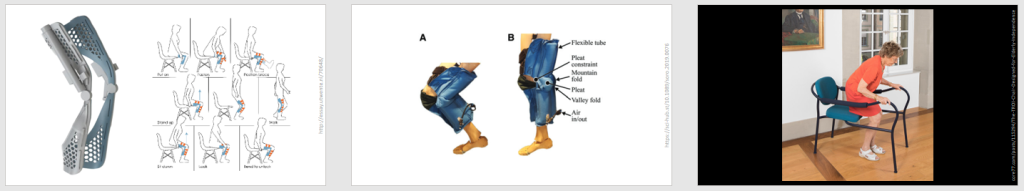

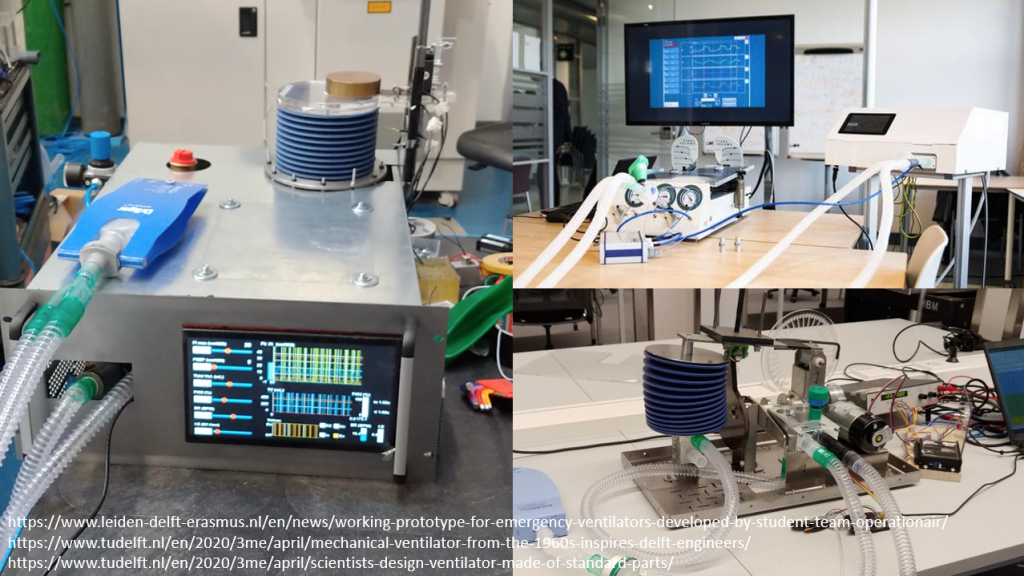

What of the case of the get-up-chair combined with two knee orthoses? What when you have A/X, A/Y, and B/Z? Could that make sense? Yes, I think so. In this case, there is a ‘wildcard’ concept. This could be a sound strategy in cases where there seems to be an obvious best option for one or a set of aspects (in this case: a powered knee orthosis). The function of the wildcard concept, then, is to check/justify that assumption. Trying to find the wildcard by asking ‘What do my two ideas have in common?’ can be a way to discover hidden or unconscious assumptions (and thus also, to find ‘more creative’ options). The emergency Covid ventilators also fall in this category, with only one departing from ‘modern, digital control system’.

(Examples from my slide deck of concept set examples)