When presenting the results of a design project, including a prototype test, I tend to recommend this chapter order:

- Concepts and Selection

- Final Design

- Test / Validation

This order is based on typical peer reviewed papers presenting the ‘design and validation’ of ‘a novel device’ or something. It also assumes a substantial difference between the final design and the chosen concept that is not the direct outcome of exploratory testing with a prototype. This order works well when the test is aimed at validating a specific part of (the performance of) the design. The final design, in this set-up, functions as a type of hypothesis, that is then empirically tested.

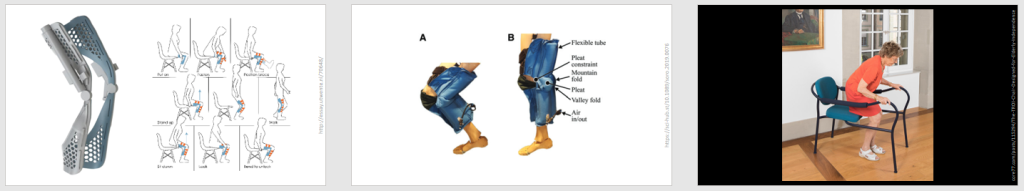

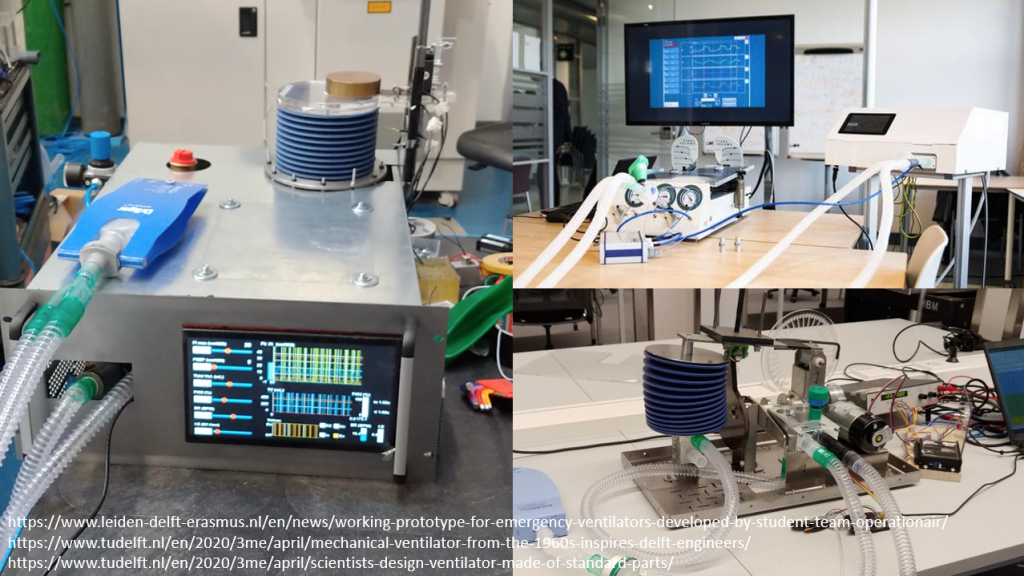

In a course that I teach where students usually dive right into prototyping after concept selection, this order doesn’t always work. And it’s confusing for them. Especially for those students who end up effectively using (early versions of) their prototype as a sketch model to discover things about their concept and to iteratively develop their design. There is also little time available in this project (and too little technical knowledge amongst these particular students) to really develop the design as a whole very much after the concept selection.

In these cases, it would probably work better to change the order:

- Concepts and Selection

- Prototype test

- Final design

You might even skip the ‘final design’ section entirely in favour of a discussion of future development. The prototype test, then, becomes not so much a focused validation of one key element within a larger complex design, but more an exploration and/or proof op principle of the chosen concept, more a validation of (the choice for) a certain solution principle than of a full design.