I just ran my first ungraded course. Obviously, I did it all wrong. Nonetheless, it was wonderful. I’ve never had better conversations with students about what they take away from a course.

In this post, I want to write down some first rough thoughts before the experience fades, also in preparation for the Ungrading as Emancipation track at MYFest.

About the course

KT2700 ‘Designing Medical Technology’ is an introductory design course in the 2nd year of the ‘Clinical Technology’ BSc programme at Delft University of Technology. It’s a group project, with 90 students in 18 groups of 5. There’s clinical and technical experts that come by for one-time meetings with each group, but I mostly teach this course by myself. The course runs for 7 weeks, with three 4-hour afternoons of class time each week.

Students choose a problem to work on, do problem analysis, develop concepts, practice drawing, and conduct a simple empirical validation of their design.

My approach to ungrading

As this was my first real course-wide ungrading attempt, I wanted to play it semi-safe and use a common, tried and tested model. In essence, this meant I replaced my assessment of the final report with a self-assessment by each group, that we discussed in a final 20 minute meeting. I did what Jesse Stommel does and told my students that although I reserve the right to change a grade, I fully intended to follow their proposals. (And in the end, I really did not change anyone’s self-determined grade.)

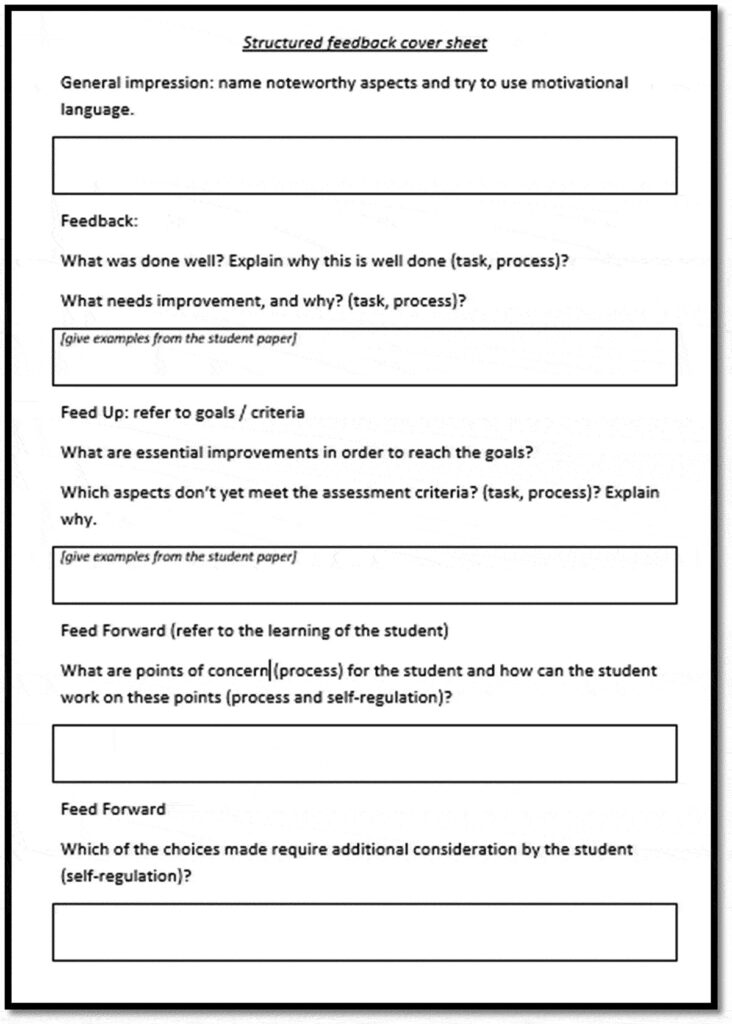

This course already contained a number of rounds of peer feedback on intermediate results. This year I added a kick-off workshop in which I asked students what they hoped to get out of the course, and what their personal challenges and goals were. I also added a (very light-weight and informal) mid-course reflection that asked students to think about how the course was going and what they were learning.

So, what did I learn?

1. First, nothing changed

I expected revolution from day one. I was super excited to blow my students’ minds in the introductory lecture with how they’d determine their own grades. Education as the practice of freedom! Equity! Rainbows and unicorns!

Yeah, not so much. The first few weeks, nothing changed. The course felt very similar to previous years. At week 5 or so, I was feeling decidedly disappointed.

Looking back, my expectations were pretty naïeve, of course. These students are so used to just doing what they’re told, getting the grade, and moving on. It was foolish to think that students can go from paint-by-numbers to full autonomy in a few short weeks.

I also realized that teacher-assigned grades are not the only thing that determines the overall character of a course. (No shit, Sherlock.) The structure I set up, with frequent peer-review assignments and deadlines, including review questions that gave the impression that there were ‘right’ or ‘correct’ ways of doing things, worked against a culture of freedom, exploration, and self-direction. I also have a lot to learn in how I respond to student questions that assume or look for a single right answer. I’m not yet so good at responding to those in a way that ignores or challenges those assumptions.

In other words, students just did the work as usual. And they still asked a lot of questions in the category ‘How do you want us to do it?’ instead of feeling free to decide for themselves. They asked to be told what to do and they did what they were told. Just like in previous years.

2. Then, everything changed

Ungrading really is transformative. Even though the students were behaving as usual in those first weeks of the course, for me my relationship with them felt completely different from the get-go. And the way the course ended transformed the experience for students as well.

Throughout the course, I felt a lot better about the way I was coaching students. Previously, I was pushing them to take risks, knowing that it might lead to output that I had to rank lower than it could have been ranked if they took the safe approach. That felt massively unfair. As betrayal, almost. And that feeling was completely gone. Even if the students were still a bit too focused on doing it right, and according to my standards, I was much more free and able to direct their attention to what they were actually learning, and to prioritize learning experiences over polished results in how I advised them.

And then I sat down to read the group self-assessments and individual reflections. Oh, boy. So much good stuff. Responding to a very general prompt, many students pointed out the exact things I would list as the core lessons for this course. And many students described learning experiences that started with apprehension, worry, or expecting not to be interested, moving through initial surprises and a growing sense of skill and comprehension, to outright enthusiasm, pride, and consequences for how they saw their future after graduating from the programme.

And then, I sat down to talk with them about all this. Those two afternoons of final meetings were some of the best conversations I’ve ever had with students. A lot of students mentioned how they rarely think about what they’d learned so effectively either. “Usually, when you hand in a report you hope to never have to see it again,” one student said. “But the way we discussed our end-results with other groups this time, and looking back at what we delivered together, was really fun and valuable.”

I’ve had final meetings after the end of a project in other courses. But those were mostly me explaining and justifying a grade. Those did not feel like conversations between equals. But these were real, open discussions.

3. Self-grading is still grading

In those final meetings I had with student groups about their reflection and self-assessment, many students explained their grade in comparative terms. They were still ranking. A few also asked me – after I’d written down their self-determined grade – whether it matched what I would have given them. They wanted to know wheter the grade was ‘correct’. I told them I have no clue what a ‘correct’ grade is anymore.

Most students didn”t really know how to translate their assessment of what they’d learned and accomplished (or not) into a single number. At the time, I felt a bit guilty for not giving them more guidance. Later I realized that this was the whole reason for not wanting to grade them in the first place: it’s impossible to distill a multidimensional set of qualitative judgements into one unidimensional number.

I don’t know yet whether my conclusion from this is that next time I want to go with a pass/fail model, or that I should accept this cognitive dissonance because the attempt to come up with the ‘right’ grade does seem to serve as an effective means of stimulating evaluative reflection and in-depth comparison with others’ work.

Side-note: the Dunning-Kruger effect

In general the level of grades was half a point higher than in previous years (the average rose from 7.8 to 8.3). That effect was less strong than I’d expected. And in any case, I really don’t care. The students did great work and learned lots. Who cares about the numbers?

But I also got the strong sense that there had been a reversal at the top end. Many of the self-given 8/10s would have been 9/10s if I had done the grading, and most 9/10s would have been 8/10s.

The Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias whereby people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability. Some researchers also include in their definition the opposite effect for high performers: their tendency to underestimate their skills.

Wikipedia

So yeah. That seems to be relevant for self-grading . At least in the context of projects, where it’s not a question of self-assessing correctness on something like exam questions, but an overall, holistic judgement of open-ended work.

4. Self assessment in groups can be problematic

One of the bigger ‘Oh, crap!’-moments in this course was when I realized that I was putting students in a difficult situation with self-grading as a group. I don’t think I ever read anything ungrading in group projects, where students have to come up with a grade proposal together as a team. In groups that didn’t get along so well, this led to issues. And even in groups that worked well together, it could lead to friction.

In one case, this led (almost) to a tragic situation with a student who’d had some issues with the group work because of his autism, but also learned a ton by working through those issues (and taught me something in the process, which I wrote about elsewhere), that still wanted to grade himself lower than the other group members because he had ‘contributed less’. Luckily I didn’t need to step in. Another member of his team would’t let him be that unfair to himself. (Students are awesome.)

5. It’s the reflection, stupid!

Earlier, I wrote:

We want our students to learn to evaluate their own work critically. The best way to do this is by practising evaluating their own work. But it is difficult to have students do this honestly when it is ultimately our evaluation that counts.

Me, in a column on ungrading for the Delta, TU Delft’s ‘journalistic platform’, informed by the work of D Royce Sadler.

When we grade our students, we take one of the most important acts of learning away from our students by doing it for them: practicing judgement. Even in its most basic, mistake-laden form (i.e. what I did in this course), ungrading makes students actually responsible for their own learning by putting the final say in their hands.

If, whatever happens during a course, in the end it’s our decisions that count, then what reason do students have to really think about the quality of their work? Why reflect seriously if the outcome of that reflection doesn’t matter, and it’s someone else’s judgement and only that other’s judgement that matters? If someone else is going to tell you what the conclusion of your own reflection should have been?

Ungrading breaks that power structure. It breaks that adversarial relationship. It emancipates. Education as the practice of freedom. Rainbows and unicorns, after all.